Honoring to

Dignify Black Music

R. Nathaniel Dett eloquently stated in his Bowdoin Literary Prize Theses (Harvard University), “It is imperative, in my opinion, for people who are sincerely interested in the Negro and his one unmistakable contribution to American civilization, to use every opportunity to dignify the music of this people, not merely by encouraging the Negro to sing his folk songs in their truly beautiful primitive form, but also by encouraging him to show their possibilities for use as themes for anthems, oratorios, and even operas.” One may ask, “Why should we explore a project like this?” Here’s why…

There is great familiarity with Negro spirituals and work songs of the mid-seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. From the cotton and tobacco fields of Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee to the rice fields of the Lowcountry, these genres became a response of the enslaved who were taken from their homeland, against their will, while the entire world turned their heads. With the bounty of these rich, idiomatic Black musical genres, one may also ask, “Is it necessary to have a musical account of Black ancestry beyond the idiomatic styles?” The response is “Yes!” for, there is more to Black music history than “Go Down, Moses” and “Take the A-Train.”

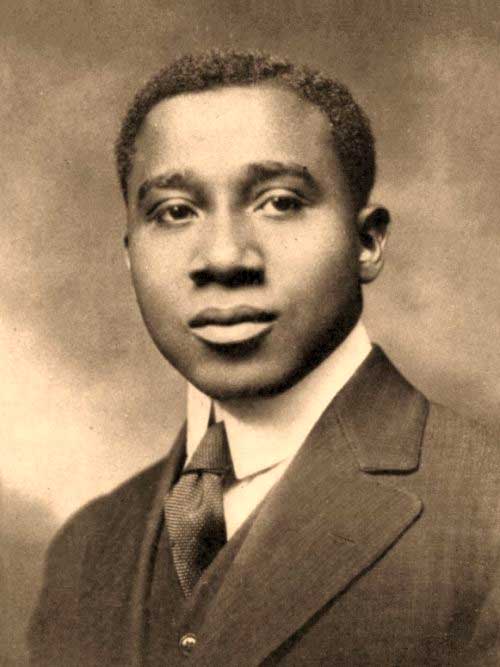

R. Nathaniel Dett

Requiem for Colour is a unique work due to the incorporation of Black idiomatic genres within the Western European style of composition. The composer feels its uniqueness is comparable to “A German Requiem” by Brahms (who gifted his people with a mass honoring loved ones in their native Germanic tongue), or “Missa Criolla” by Argentine composer Ariel Ramírez (who gave the world a mass in Spanish and Latin styling). Since the works of Brahms and Ramírez, there have been other significant requiem settings by composers of color such as Gabriela Lena Frank, Carlos Simon, and most recently Damien Geter.

Frank’s Conquest Requiem (2017) is inspired by a true story of a young Nahua woman (Malinche) who was enslaved by the Spaniards, became Cortés’ mistress, and gave birth to one of the first mestizos (mixed-race) of the New World. Gabriela Lena Frank speaks of the complexity of Malinche’s life by saying, “she has been variously viewed as a feminist hero who saved countless lives, [a] treacherous villain who facilitated genocide, [a] conflicted victim of forces beyond her control, or as [the] symbolic mother of the new mestizo people.”

Simon’s Requiem for the Enslaved (2021) honors the men, women, and children owned and sold by Georgetown University (a Jesuit university). Georgetown’s tradition of excellence and rich history is conflicted by its involvement with enslavement. Through collaboration with Georgetown, Simon skillfully blends the music of the Catholic Church, Spirituals, rap and spoken word in an effort to reconcile the university’s tainted past.

Geter’s An African American Requiem (2019) is a twenty-movement work based on the traditional Latin requiem liturgy infusing Spirituals and modern declarations relating to racial violence against African Americans. Included in these declarations is a setting of Ida B. Well’s speech Lynching is Color Line Murder and Eric Garner’s exclamation that will be forever etched in the minds of people around the world, “I Can’t Breathe.”

Requiems have been composed since the Medieval period. To date, there are sure to be thousands with many of them written by Anglo, non-composers of color. To pose the question once more, “Is it necessary to have a musical account of Black ancestry beyond the idiomatic styles?” The answer, yet again, is “Yes!”

Given the few examples of other significant works mentioned, Ames’ Requiem for Colour is just as significant as the masterworks by his contemporaries. Not only will the requiem honor the memory of Black Americans who have died from entrapment, violence, and civil atrocities, but the masterwork will also function as a clarion call for justice, equality, and freedom. Like the requiems of Frank, Simon, and Geter, Ames’ masterwork is the founded upon Western tradition of composition; but what makes it “colourful” is the incorporation of musical traditions indicative of the black culture such as Spirituals, Jazz, Hip Hop, Rap, and Gospel.